Much as I’ve wanted to avoid this debate about Islamophobia and current members of the presidential administration, as a research and educator in terrorism studies there are some things I need to point out.

1). Islamist extremists have been blowing up themselves and others in dozens of countries for the last half century, including our own. Nobody I know or care about is trying to minimize this reality. That said, mis-diagnosing the nature of this threat as one that applies throughout all of Islam – and formulating polices based on false perceptions – is dangerous and ill-advised. Criticisms of those misperceptions are not “libtard apologists for Islam” or any such nonsense. Many experts in security studies and counterterrorism have been pushing back against the Islamophibic primarily because they want to see a more effective counterterrorism approach, one based on evidence and thorough intelligence analysis rather than fear and hysteria.

2).   No religion is immune to the efforts by a small minority of believers to use sacred texts to try and justify violence against others. Within any religion, the majority of the faithful reject interpretations of their sacred texts that are used to try and justify violence against others. Those rejectionists of violence are vital allies in combating religiously-oriented terrorism.

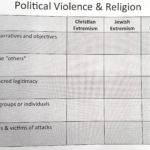

3). Anyone who can’t fill out the chart below (re: Islamist, Jewish and Christian extremists) doesn’t know enough yet about the intersections of political violence and religion that are common across all major faiths. The fact is that extremists within any religion justify among themselves the need for violence in order to “defend the faithful”, to “inspire others” and to serve God’s will, among other goals. This kind of comparative analysis is extremely unpopular among the anti-Islam crowd, but it is crucial to step away from the kinds of inferred cultural superiority that blinds accurate analysis of the threat.

4). Islam is not a monolithic entity. The threat of jihadism (and the violence associated with it) is rightly situated within a series of nested levels of discourse and divisions within Islam.

- Islam – A global religion of 1.8 billion people, with large concentrations in Southeast Asia, the Middle East and North Africa. There are many divisions within, including Sunni, Shia, Sufi, and Deobandi. There is considerable animosity between Sunni and Shia Muslims.

- Sunni (roughly 85% of Muslims) follow the example of Muhammad and believe that the first four caliphs were legitimate rulers. Sunnis have no central religious organization or centers of authority.

- Shia (roughly 15% of Muslims) believe that only the descendants and relatives of Muhammad are the legitimate rulers of all Muslims.

- Sufi are mystics, found among both Sunni and Shia Muslims, who seek to draw close to God through various rituals

- Deobandi is a popular revivalist movement among Sunni Muslims, particularly in Asia, that emphasizes scholastic traditions.

- Islamism: An ideological argument, supported by some Muslims, that politics and society must be organized according to Islamic doctrine

- Salafism is a Protestant-like fundamentalist version of Sunni Islamism that seeks to purify Islam from outside cultural influences. Salafists (also Wahhabists) want politics and society to be organized according to the ways in which the religions “forefathers” (salaf) lived, including the prophet Muhammad and the first few generations of Mulims.

- Salafi-Jihadism is a subset of Salafism whose believers try to justify using violence to achieve the Salafist political agenda. Al-Qaida, the Islamic State, and other terrorist groups support this Salafi-Jihadist ideology.

- Salafism is a Protestant-like fundamentalist version of Sunni Islamism that seeks to purify Islam from outside cultural influences. Salafists (also Wahhabists) want politics and society to be organized according to the ways in which the religions “forefathers” (salaf) lived, including the prophet Muhammad and the first few generations of Mulims.

5) As thousands of scholars have shown, there are many drivers of conflicts and political violence (including insurgency, terrorism, civil war and genocide) beyond religion. An argument that there is something inherently violent within all of Islam ignores the fact that violence is rare among the 1.8 billion Muslims worldwide. If Islam was truly a major factor in violence, Southeast Asia (where there are far more Muslims than in the Middle East) would be embroiled in the same kinds of conflicts we see in Iraq and Syria.

6). Images and stories from politically-oriented media outlets and individuals who misinterpret events and factual information provide an all-too-easy confirmation bias for viewers. Further, from decades of research in psychology, we know that people prefer information consistent with their beliefs, views and prior behaviors, and avoid information that’s inconsistent. Provocative narratives like Islamophobia don’t have to be true to be believed. The creation of massive echo chambers, in which a person can get all their information about religion and conflict from like-minded sources, has led to a dangerous polarization in the public debate about how to understand and effectively counter the threat of jihadist terrorism.

7). The bottom line: Within Islam, the Salafists have for many centuries argued that their conservative, fundamentalist interpretation of the Koran should be adhered to by all Muslims. The Salafists are a relatively small (but significant) minority within the overall Muslim world. Among the Salafists, a small minority of jihadists employ a narrative that tries to justify the use of violence toward achieving this goal. The majority of Salafists – and indeed the overwhelming majority of Muslims worldwide – reject this Salafi-Jihadist argument. These rejectionists are necessary allies in combating Salafi jihadist terrorism promulgated by the likes of al-Qaida and the Islamic State. Furthermore, global jihadist ideologues (like al-Baghdadi and al-Zawahiri) are constantly trying to justify the killing of bystanders (including Muslim women and children) and have difficulties finding credible Islamic scholars to support these actions. They often twist and misrepresent ancient texts and fatwas (including those of 13th century cleric Ibn Taymiyyah) to justify their type of violence. The illegitimacy of this theological twisting is also a source of animosity and rejection among the overwhelming majority of the Muslim world. This is why it is misguided and counterproductive to portray the rejectionists of jihadism as our enemies. If anything, they have just as much interest as we do in defeating this violent ideology – not the least of which is because the data clearly show that far more Muslims have died than non-Muslims from Salafi-Jihadists attacks over the past two decades.

James J.F. Forest, Ph.D. is professor in the School of Criminology & Justice Studies at UMass Lowell, Visiting Professor at the Fletcher School of Law & Diplomacy, and Senior Fellow at the Joint Special Operations University. His latest book is Essentials of Counterterrorism (Praeger, 2016).